Location Transparency with Akka

14 December 2016. Tags: Akka, Scala, Kubernetes and Docker.

In this post I am going to talk about one of my favourite features of the Akka toolkit: Location Tranparency.

“What location transparency means is that whenever you send a message to an actor, you don’t need to know where they are within an actor system, which might span hundreds of computers. You just have to know that actors’ address.” (from Akka.NET docs)

We will see how a local application can be split into distributed components that can be scaled independently. This can be achieved by changing only startup code, configuration and deployment, but leaving the main code untouched.

Our application will expose an HTTP API to greet people, and it will be written in Scala. The full source code can be found at https://github.com/paoloambrosio/experiments/tree/akka-location-transparency, as a series of three commits going from a local to a clustered application. The project can be deployed as Docker containers and includes Kubernetes configuration files that we will use to play with the application.

Sometimes we’ll use *nix commands to run the example, so if you are on Windows you’ll have to either install Cygwin or figure out the corresponding command to run.

Common components

The core of this simple application are just three classes. The naming convention followed in this project highlights the purpose instead of the functionality provided. This of course wouldn’t be the case for a real application, but it helps understanding the example.

The FrontendRestApi trait defines the HTTP API:

trait FrontendRestApi extends JacksonSupport with BackendApi {

def routes = (path("greet" / Segment) & get) { name =>

complete(greet(name))

}

}

The BackendApi trait is a facade to hide the message-based implementation of the communication with the backend service, used by FrontendRestApi like we have just seen:

trait BackendApi {

import BackendApi._

def backend: ActorRef

implicit def backendTimeout: Timeout

def greet(name: String): Future[Greeting] =

backend.ask(Greet(name)).mapTo[Greeting]

}

object BackendApi {

case class Greet(name: String)

case class Greeting(message: String)

}

The Backend actor implements our greeting service:

object Backend {

def props = Props(new Backend)

}

class Backend extends Actor with ActorLogging {

import BackendApi._

override def receive = {

case Greet(name: String) =>

log.info("Greeting {}", name)

sender() ! Greeting(s"Hello, $name")

}

}

Not a single line of code will change in those files when going from centralised to distributed deployments.

Centralised deployment with local actors

(Commit ee30902)

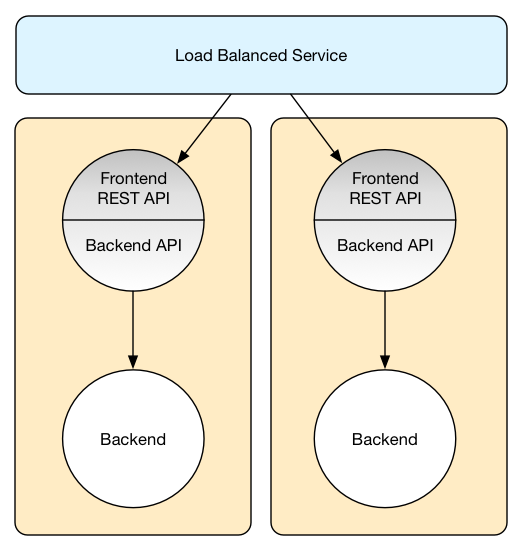

Wiring between frontend and backend for this simple case is defined in the startup code. A backend actor is created locally and its reference is simply passed to the frontend component. Communication between the two never crosses the application boundaries.

object FrontendApp extends App

with HttpServerStartup with FrontendRestApi {

// ...

override val backend = system.actorOf(Backend.props, "backend")

// ...

}

The Docker container is simply created by a combination of JavaAppPackaging and DockerPlugin. The Kubernetes service and deployment files are standard for a load-balanced Web application and can be found in the kubernetes/ directory.

We can test the application locally by running it from SBT (each command on a separate terminal)

1$ sbt frontend/run

2$ curl http://localhost:9000/greet/World

{"message":"Hello, World"}

or we can deploy it on a local Kubernetes cluster using Minikube.

$ eval $(minikube docker-env)

$ sbt docker:publishLocal

$ kubectl create -f kubernetes/

$ curl $(minikube service frontend-service --url)/greet/World

{"message":"Hello, World"}

Of course we can also scale nodes like we would do for any service deployed in Kubernetes.

$ kubectl scale --replicas=3 deployment/frontend-deployment

$ curl $(minikube service frontend-service --url)/greet/World

{"message":"Hello, World"}

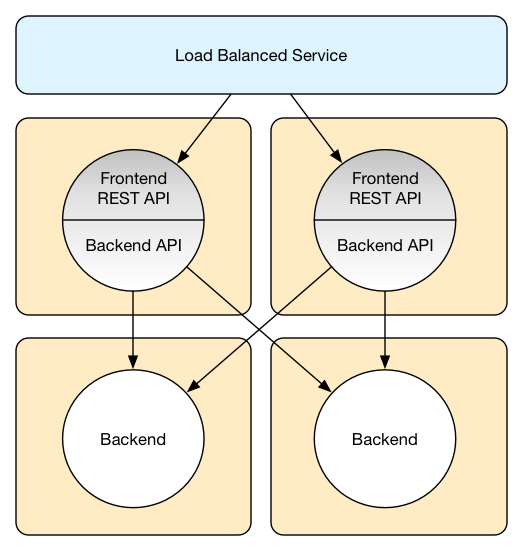

Decentralised deployment with remote actors

(Commit 5735a10)

What happens now if we want to separate frontend and backend to be able to scale them independently? With Akka that is straightforward.

First we need to enable Akka Remoting:

akka {

actor {

provider = remote

}

remote {

enabled-transports = ["akka.remote.netty.tcp"]

netty.tcp {

hostname = ${app.remote.interface}

port = ${app.remote.port}

}

}

}

app {

remote {

interface = "127.0.0.1"

interface = ${?REMOTE_INTERFACE}

port = 0

port = ${?REMOTE_PORT}

}

}

In the frontend application we then configure the local backend actor to be a router instead, so that messages are transparently routed to remote backend actors, and create the actor reference from that configuration.

akka.actor.deployment {

/backend {

router = round-robin-group

routees.paths = ${app.backend.nodes}

}

}

app.backend.nodes = []

object FrontendApp extends App

with HttpServerStartup with FrontendRestApi {

// ...

override val backend = system.actorOf(FromConfig().props(), "backend")

// ...

}

Of course we also need to create a separate application to host the backend actor.

object BackendApp extends App {

// ...

system.actorOf(Backend.props, "backend")

// ...

}

We can now run the following commands on different terminals to see it in action:

1$ REMOTE_PORT=2551 sbt backend/run

2$ REMOTE_PORT=2552 sbt backend/run

3$ REMOTE_PORT=2553 sbt frontend/run \

-Dapp.backend.nodes.0=akka.tcp://example@127.0.0.1:2551/user/backend \

-Dapp.backend.nodes.1=akka.tcp://example@127.0.0.1:2552/user/backend

4$ curl http://localhost:9000/greet/World

{"message":"Hello, World"}

This is really exciting! With no changes to the core of the application we separated frontend and backend components.

In the example code on GitHub I’ve gone a bit further and got rid of the ugly system properties (see trait BackendPathsConfig) and made it work seamlessly with Kubernetes. This gives us the opportunity to see how routers can be configured programmatically.

object FrontendApp extends App with BackendPathsConfig

with HttpServerStartup with FrontendRestApi {

// ...

override val backend = system.actorOf(RoundRobinGroup(backendPaths()).props(), "backend")

// ...

}

After those changes we can pass the backend nodes as an environment variable

1$ REMOTE_PORT=2551 sbt backend/run

2$ REMOTE_PORT=2552 sbt backend/run

3$ REMOTE_PORT=2553 BACKEND_NODES=127.0.0.1:2551,127.0.0.1:2552 sbt frontend/run

4$ curl http://localhost:9000/greet/World

{"message":"Hello, World"}

or run it on Kubernetes using a custom startup script to pass those environment variables (in project/Docker.scala).

The problem with this configuration is that the backend router in our frontend nodes will route only to backend nodes already deployed when the application starts. All backend nodes started later will not be contacted unless the frontend applications are restarted with a new configuration. It is possible to add routees to a router after it is created but this would add unnecessary boilerplate, given that the same behaviour can be better achieved with the out-of-the-box clustering capabilities.

Decentralised deployment with a cluster

(Commit 9bd3fe1)

To achieve an elastic behaviour we can use Akka Clustering. Even in this case though changes will be minimal and the main classes will stay untouched.

On top of the Remoting configuration, we need to enable Clustering. The main change is the actor provider from “remote” to “cluster”. In this example I’m disabling metrics and enabling auto-downing because it’s not a production instance (more on the Akka documentation). This will have to be done in both frontend and backend applications, since they will all become part of the same cluster.

akka {

actor {

provider = cluster

}

cluster {

// seed-nodes = [ ... ] will be filled up programmatically

metrics.enabled = off

auto-down-unreachable-after = 5s

}

}

The backend router in the frontend application will be reconfigured with cluster support, and basically that is it!

akka {

actor {

deployment {

/backend {

router = round-robin-group

routees.paths = ["/user/backend"]

cluster {

enabled = on

allow-local-routees = off

}

}

}

}

}

In a similar way to what we have done for Akka Remote we can pass akka.cluster.seed-nodes as a system variable, or programmatically enrich the configuration from an environment variable before the actor system is created (by ClusterSeedNodesConfig trait in the example).

trait ExampleApp extends ClusterSeedNodesConfig {

val actorSystemName = "example"

val config = ConfigFactory.load()

implicit val system = ActorSystem(actorSystemName, configWithSeedNodes)

val log: LoggingAdapter = system.log

}

Again we can run it manually

1$ REMOTE_PORT=2551 sbt backend/run

2$ REMOTE_PORT=2552 CLUSTER_SEEDS=127.0.0.1:2551 sbt backend/run

3$ REMOTE_PORT=2553 CLUSTER_SEEDS=127.0.0.1:2551,127.0.0.1:2552 sbt frontend/run

4$ curl http://localhost:9000/greet/World

{"message":"Hello, World"}

or on Kubernetes

$ eval $(minikube docker-env)

$ sbt docker:publishLocal

$ kubectl create -f kubernetes/cluster-service.yaml

$ kubectl create -f kubernetes/backend-deployment.yaml

$ kubectl create -f kubernetes/frontend-service.yaml

$ kubectl create -f kubernetes/frontend-deployment.yaml

$ curl $(minikube service frontend-service --url)/greet/World

{"message":"Hello, World"}

If we look at the logs for each node of the cluster, we can see that the backend node comes up first, can’t find any other node and decides to elect itself as the leader. The frontend node starts later and contacts the backend node to join the cluster.

$ for p in $(kubectl get pods -o name --sort-by='metadata.creationTimestamp'); do

> echo "*** $p ***"

> kubectl logs $p | grep 'Cluster Node' | cut -d ' ' -f 2,3,9-

> done

*** pod/backend-deployment-1282131813-g2ut4 ***

[12/14/2016 06:58:40.319] - Starting up...

[12/14/2016 06:58:40.418] - Registered cluster JMX MBean [akka:type=Cluster]

[12/14/2016 06:58:40.419] - Started up successfully

[12/14/2016 06:58:40.696] - Node [akka.tcp://example@172.17.0.4:2551] is JOINING, roles []

[12/14/2016 06:58:40.816] - Leader is moving node [akka.tcp://example@172.17.0.4:2551] to [Up]

[12/14/2016 06:58:51.299] - Node [akka.tcp://example@172.17.0.5:2551] is JOINING, roles []

[12/14/2016 06:58:51.675] - Leader is moving node [akka.tcp://example@172.17.0.5:2551] to [Up]

*** pod/frontend-deployment-1898507028-b1emx ***

[12/14/2016 06:58:49.984] - Starting up...

[12/14/2016 06:58:50.255] - Registered cluster JMX MBean [akka:type=Cluster]

[12/14/2016 06:58:50.257] - Started up successfully

[12/14/2016 06:58:51.965] - Welcome from [akka.tcp://example@172.17.0.4:2551]

Let’s see what happens now when we scale the backend deployment. The second backend node comes up and contacts the first backend node to join the cluster, just like the frontend node did.

$ kubectl scale --replicas=2 deployment/backend-deployment

deployment "backend-deployment" scaled

$ for p in $(kubectl get pods -o name --sort-by='metadata.creationTimestamp'); do

> echo "*** $p ***"

> kubectl logs $p | grep 'Cluster Node' | cut -d ' ' -f 2,3,9-

> done

*** pod/backend-deployment-1282131813-g2ut4 ***

...

[12/14/2016 07:04:30.552] - Node [akka.tcp://example@172.17.0.6:2551] is JOINING, roles []

[12/14/2016 07:04:31.495] - Leader is moving node [akka.tcp://example@172.17.0.6:2551] to [Up]

*** pod/frontend-deployment-1898507028-b1emx ***

...

*** pod/backend-deployment-1282131813-ezi4z ***

[12/14/2016 07:04:30.176] - Starting up...

[12/14/2016 07:04:30.267] - Registered cluster JMX MBean [akka:type=Cluster]

[12/14/2016 07:04:30.268] - Started up successfully

[12/14/2016 07:04:30.603] - Welcome from [akka.tcp://example@172.17.0.4:2551]

If we now issue a couple of requests to our REST API, we can see that the frontend node has realised that a second backend node has joined the cluster and has started routing traffic to it using a round-robin algorithm.

$ curl $(minikube service frontend-service --url)/greet/World

$ curl $(minikube service frontend-service --url)/greet/World

$ for p in $(kubectl get pods -o name --sort-by='metadata.creationTimestamp'); do

> echo "*** $p ***"

> kubectl logs $p | grep 'World' | cut -d ' ' -f 2,3,6-

> done

*** pod/backend-deployment-1282131813-g2ut4 ***

[12/14/2016 06:58:58.405] Greeting World

[12/14/2016 07:09:04.086] Greeting World

*** pod/frontend-deployment-1898507028-b1emx ***

*** pod/backend-deployment-1282131813-ezi4z ***

[12/14/2016 07:09:02.099] Greeting World

Conclusion

We didn’t go much in detail on how Akka Remoting or Clustering work. The official documentation is very detailed, but in this article I wanted to provide a cross-cutting view. Hopefully it inspired you to keep your code clean to support Location Transparency out of the box.

Happy hakking!